Are you Ignoring Power?: How Power Training Can Help Your Lifting

If you’re not training power, you’re missing out on some very simple gains to strength and performance.

Whether you’re an actual athlete or you’re just in the gym trying to get strong and improve yourself, power training isn’t optional. It’s one of the most overlooked ways of improving your performance and unlocking your body’s varied athletic potential.

Whether you’re the next Olympic sprinter or the most average of Joes, we’re going to let you in on why you need power and how to develop power.

What is Power?

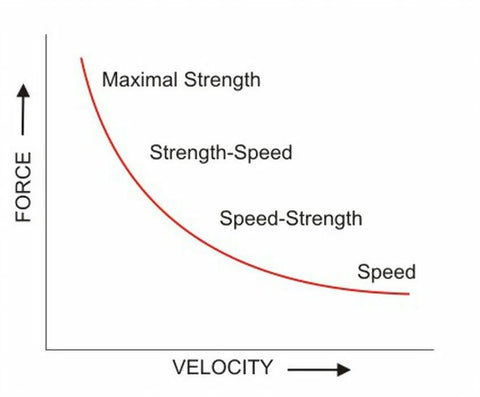

Power is the trait that comes from overlapping speed and strength. It’s the ability to produce force rapidly against external resistance – even as little as gravity on your own body.

This is the kind of training that occurs between absolute strength (like a max effort squat) and absolute speed (like a max sprint). This is the strength-speed continuum which has separate goals at either end, but they work together, rather than just competing.

Every exercise you do will fall somewhere on this continuum, and power overlaps with both extremes – strength and speed.

Why Does Power Training Matter?

Your power is the ability to produce force rapidly. This isn’t just useful for jumps; it carries over to every type of exercise.

Studies already tell us that the ability to rapidly produce force in the bottom of a squat is a key for elite powerlifters. Equally, Olympic weightlifting is a sport that is all about moving heavy weight rapidly.

Track and field are both reliant on great rapid-force production, where ballistic/throwing sports require huge acceleration of a weighted implement. In track, accelerating yourself relies on producing huge force against the block/floor.

Finally, team sports benefit from power in a huge way. Power is important for sprinting and jumping abilities but is also plays a role in the ability to change direction by absorbing and producing force rapidly.

Power and Health in Seniors

It’s not just sport performance that benefits from power. It’s also one of the key risk factors in your fall/fracture risk – and even more important as you age.

Studies tell us that power training is essential for the best possible aging process. This helps seniors stay health and avoid the risks of falls and fractures that often lead to cycles of hospitalisation.

The ability to stabilise and regain balance relies heavily on power training and reactivity. If you’re not effective at producing force rapidly, and familiar with the stretch-rebound cycle that muscles go through, your risk of injury shoots way up.

How Can you Train Power?

Strength

Power is a function of two things – your maximal force and your ability to produce a certain % of that force in a certain time.

Building strength is often the fastest way for a total novice to improve power. It’s better when combined with specific training, but the important point is that an athlete with 200kg of maximal force will be much more powerful than one with 100kg maximal force.

The ability to squat a lot isn’t all it takes to be good with power, but it does provide a foundation for future training. Not only does it provide a larger maximum force capacity, but it strengthens the tissues that are going to be transferring this force.

Being strong is a form of resilience and force-capability in the muscles and connective tissues. When you look at the movements and muscle groups that are going to be involved a movement you want to be good at (e.g. the bench press, squat, power clean, or sprint), make sure they’re strong first.

A surplus of strength is going to be great for power output and it should be developed specifically in response to the goals you have with it.

Strength Isn’t the Only Factor or Solution!

A quick caveat. Some goals don’t reward strength if it comes at the cost of adding bodyweight. This is the big challenge for sports like basketball where jumping ability is a huge factor. This kind of movement of your own bodyweight is a challenge because adding weight is often a problem for vertical jumps.

The pay-off for strength gets less and less as the surplus gets larger. Going from a 70kg to 170kg squat makes a difference, but from 270 to 300kg will be far less so. Stay specific to your own goals and remember that what is going to help the most will change as you train.

Plyometric Training

Plyometric training is where muscles are cycled through their stretch-contract cycle in a movement. For example, the countermovement jump is about lengthening then contracting muscles to jump.

This stretch-shortening cycle is one of the key players in speed since it helps you perform repetitive movements (like running or cycling). This type of training also improves contraction speeds and can support overall power training.

There are tons of great plyometrics. Start with box jumps, which take stress off of the landing. These can be performed at any height you’re comfortable with and gradually raised over time. This will also help you work on jumping and landing mechanics to keep your knees and hips healthy.

You can progress from this kind of stationary jump to paused jumps, multiple jumps in a row, and start adding in varieties like depth jumps. As you progress, you’re adding more elasticity to the movements and more focus on absorbing and producing force.

This is one of the easiest ways to improve power and should be part of an effective warm-up for movements like squats and deadlifts, as well as the Olympic lifts. Effective plyometric and jump training improves muscle-recruitment in the long term and supports better short-term performance in strength and power movements.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gjgWFMYC0og

If you just want to get stronger and fitter, this is one of the easiest, least time-consuming ways of building power and speed. This has great carryover, while also being easy and low-load.

Speed Training to Build Better Power and Strength

Training for maximal velocity – producing force as rapidly as possible without worrying about the amount of resistance – also helps power. This is a neural change: you’re just getting used to recruiting stronger muscle fiber bundles more rapidly.

This is the kind of training you’ll do with sprints, stationary jumps, and some forms of throws with light weights. Speed always requires force and moving yourself if nothing else, but it makes for a great lower-intensity way of training the “speed” side of speed-strength.

There is also value to very specific speed training. If you’re trying to get faster in a certain movement, then general and specific speed and power training can be helpful. Sprinters don’t just do things fast to improve their 100m, they have to practice moving fast in that movement.

Perform general speed movements – like sprints and jumps for weightlifting – as well as specific speed movements.

In this example of weightlifters, this might mean explosive step-jumps as part of a well-structured warm-up, use of light power snatch/power clean variations, squat jumps, and sprints after a workout.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8Fd7tIkhRs

You can’t do everything all the time – you need to manage the load on your joints and muscles – but speed should be worked in specific and general ways.

Strength-Speed training: the middle of the continuum

When it comes to training that isn’t just speed or strength, there’s a lot of variety. How you apply these lessons and train in the middle of this continuum has a huge impact on power and is one of the most important methods for better performance!

We can roughly separate these into 3 groups, by how heavy the loading is: light, medium, and heavy.

Low-Load Power Exercise

For strength sports and gym performance, however, the vast majority of benefits are going to come from training power specifically. This is the middle of the continuum between light, loaded movements and heavy max-effort ¼ squat jumps (for example).

Th lighter side of this movement includes common GPP exercises like medball overhead throws, which are perfect for weightlifters and powerlifters to train knee/hip extension. This should also include lighter squat jumps (around 30% of 1RM back squat) and split jumps with dumbbells.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a6m1irvPilk

Medium-Load Power Exercise

This is work performed in the peak power regions of roughly 50-80% of maximum load. The science shows that there’s a strong response to this kind of training since it’s likely to be heavy enough to stimulate muscle unit recruitment without being too heavy to reduce speed/velocity too much.

You can also make these movements very specific since they allow for the loading that is going to be specific to your goal performance. Speed variations of the squat/bench/deadlift and power variations of the snatch/clean fit into this middle category.

This should also include push presses and jerks for regular athletic training and can be used specifically in weightlifting movements to build power and positional strength.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pE07wCY_j7U

These movements also provide carryover to both maximal speed and maximal strength. The improvements in the mid-range are the common ground between track athletes and strength/power athletes. Training power just makes you better at everything!

This is the heaviest a recreational gym-goer will need. If you want to get big and strong and athletic, going heavier than this is probably not necessary and combining low- and mid-load power training will carry over to performance in almost every area.

Heavy-Load Power Exercise

This is the kind of stuff that has to really be considered and measured against your goals. This is the kind of training you’d expect to see in off-season power athletes like sprinters, throwers, rugby players and American football players.

¼ squat jumps are the example we’ve already used because they’re such a good example of how heavy power training works. This is a type of maximum output, overloading movement where velocity/speed is low because load is so high.

This does have some important uses for scrums and other sports positions where maximum force output is important. For the regular gym-goer or athlete that doesn’t train for maximum force, however, it’s introducing a lot of injury risk for very little return.

Other examples include Explosive step ups from pins, compensatory power work on a flywheel, and weightlifting movements like snatch/clean pulls from blocks. These have very specific benefits but they’re not the best choice for everyone.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1rmZVMZU01w

Closing Thoughts

Power training is one of the most often-overlooked types of athletic improvement. If you’re going to the gym and not training power at least weekly, you’re missing out on benefits to everything from health to strength.

Developing a well-rounded athletic profile is amazing for its own sake, but it’s got benefits to every kind of health and fitness goal, as well as boosting sport performance massively.

If you’re not incorporating power training right now, have a think about what your goals are and which of the methods we’ve mentioned fit you. We recommend always starting towards the lower-load power movements.

If you’re just getting started, try adding in 5x3 box jumps for hip height (not foot height!) to your warm-up for squat/deadlift/Olympic lifts. You can also work with wall ball/medball overhead throws before or after a training session to develop power.

These two examples are a great place to start and power work is so fun you might just stick with it and start getting fast, stronger, and powerful!

About The Author

______________________________________________________

Professional sport/fitness writer, Weightlifter, high-performance enthusiast. Liam wears many hats, but they’re unified by a love for competition, performance, and engaging writing. You can get in touch (or hurl abuse) over at ApexContent.Org.